Nations, Power, and a New Global Balance

Artificial intelligence has long since moved beyond the stage of a simple technological innovation. By 2025, generative AI had become a central element in corporate strategies and, increasingly, a pillar of geopolitical competition. Large language models are no longer just sophisticated algorithms, but strategic assets that reflect the economic ambitions, political priorities, and technological capacities of the nations that develop and control them.

The global AI landscape at the end of 2025 and the beginning of 2026 reveals a rapid reconfiguration of power. The struggle for leadership in generative AI is not only reshaping markets, but also redefining relationships between states. Although companies remain the visible actors, the deeper reality is a competition between countries and political blocs, with the United States and China at its core, the European Union following a distinct regulatory path, and several other nations attempting to position themselves within this emerging order.

EU companies: Mistral. Middle-East companies: z-AI.

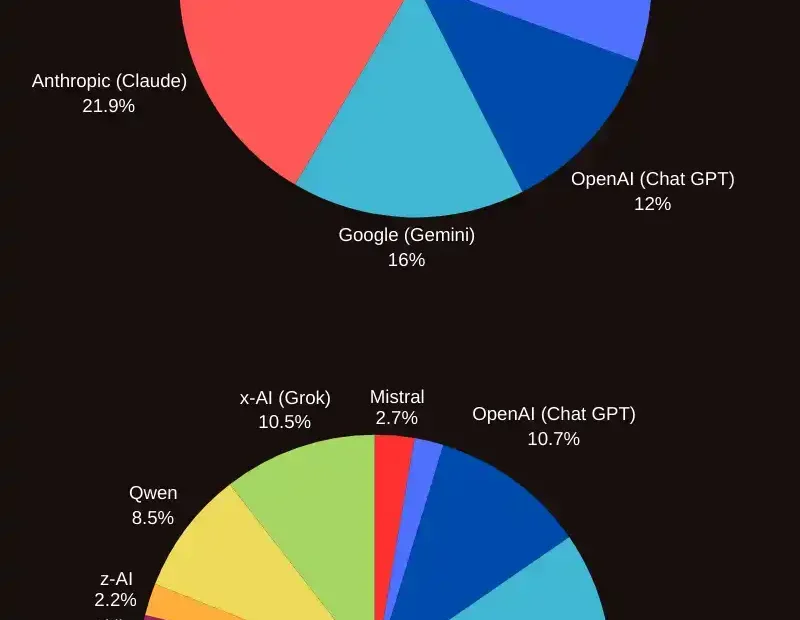

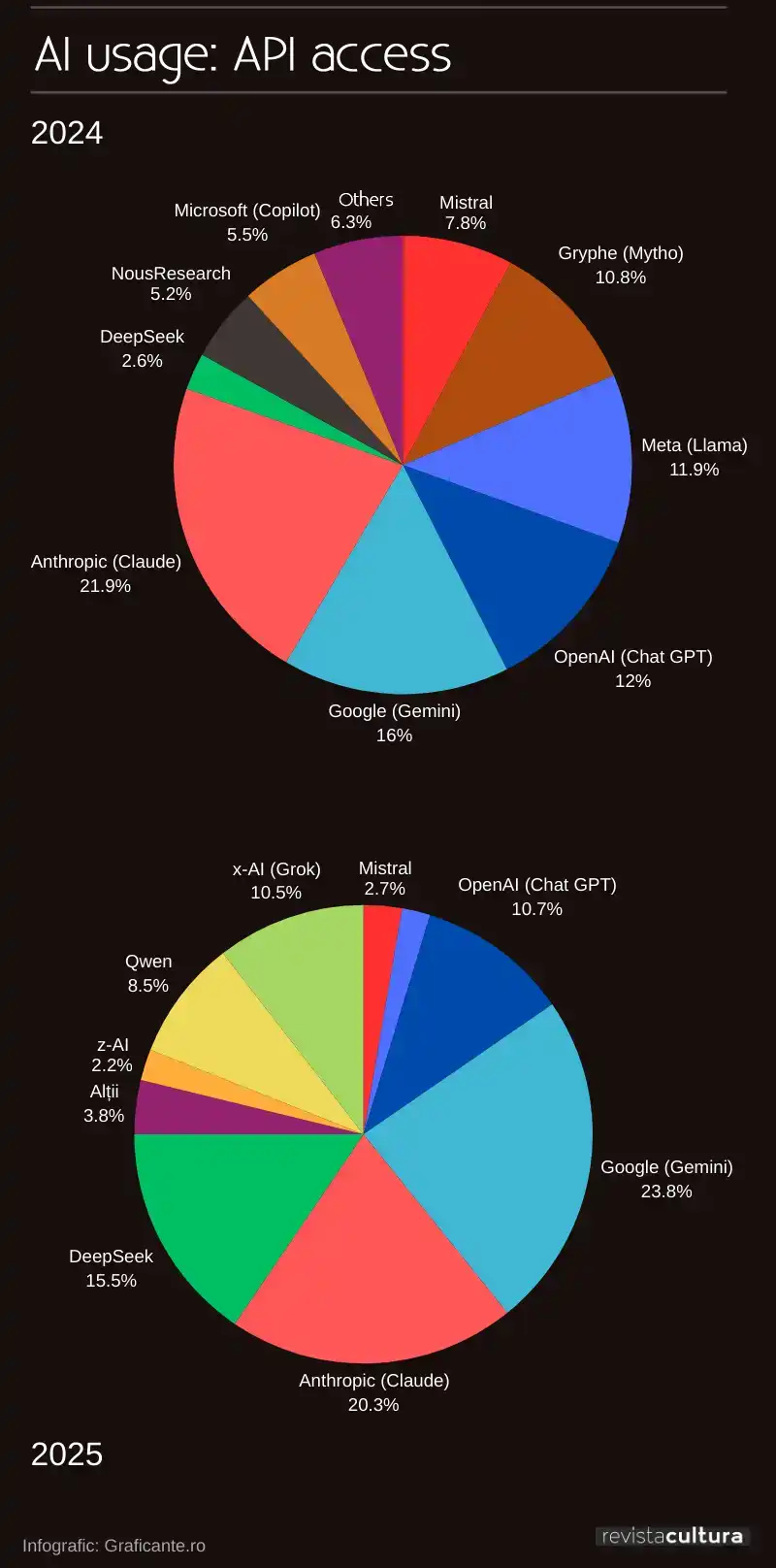

An analysis of usage data from 2024 to 2025, based largely on API traffic, shows how quickly the hierarchy has shifted. In autumn 2024, models developed in the United States overwhelmingly dominated automated AI usage worldwide. By the summer of 2025, and even more clearly by January 2026, this dominance remained substantial but no longer exclusive. Chinese-developed models had risen sharply, capturing a significant share of global automated use, while European initiatives struggled to keep pace. Or, simply, to start.

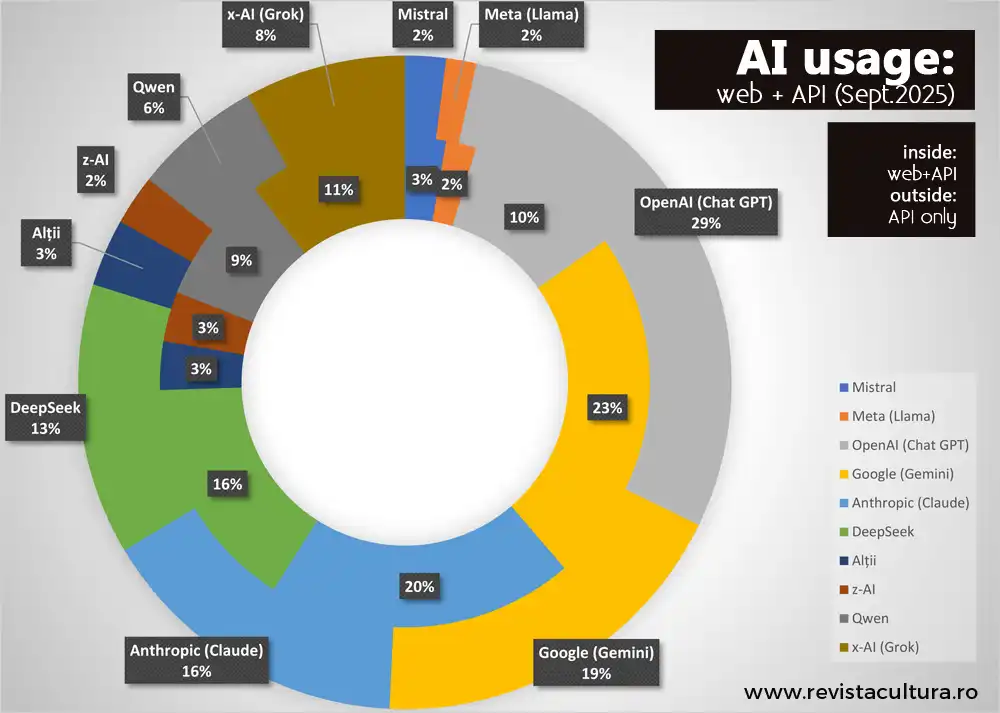

These figures must be interpreted carefully. There are, in practice, two distinct AI realities. One is the world of direct access through browsers and consumer applications, which shapes public perception and everyday interaction. The other is the far larger, less visible sphere of API usage, where AI models are embedded into platforms, services, industrial systems, and enterprise software. This second layer represents the real infrastructural backbone of the AI economy. In 2025 it accounted for roughly three quarters of global AI activity, and it is here that geopolitical dependencies are being built.

In this infrastructural domain, the United States has remained the central force. American-developed systems continue to account for the majority of global AI usage, supported by a broader ecosystem that includes cloud computing giants, semiconductor producers, research universities, venture capital, and close ties between civilian technology and state institutions. Even where market shares fluctuate between individual models, the underlying structure of the AI world-system remains heavily American. The core hardware, the dominant cloud platforms, and most of the leading foundational models are still controlled by U.S.-based actors.

At the level of direct public use, American platforms also retain a commanding presence. By the end of 2025, AI chatbots and assistants developed in the United States continued to dominate most national markets, including Europe, India, much of Southeast Asia, and the Americas. This gives the United States not only infrastructural power, but also a form of cultural and cognitive influence, shaping how hundreds of millions of people interact with AI systems on a daily basis.

Yet the most significant development of the past year has been the acceleration of China’s AI sector. In 2024, Chinese generative models played only a marginal role globally. Over the course of 2025, their share of automated AI usage expanded dramatically. By early 2026, Chinese-developed systems accounted for a substantial portion of global API traffic, placing China firmly in the position of the world’s second AI power.

This rise is not evenly distributed across the globe. Usage patterns show that Chinese models dominate overwhelmingly within China itself and have become leading systems in a number of politically or economically aligned countries, including Russia, Belarus, Iran, Syria, and Cuba. In these regions, Chinese platforms often hold market shares exceeding forty or even fifty percent. In Europe and the Americas, by contrast, their presence remains limited. The geography of AI use thus increasingly mirrors the geography of political alignment.

China’s AI strategy appears focused not only on technological competition, but also on building a parallel digital ecosystem. Heavy state investment, coordination between industry and government, and the prioritization of national technological autonomy have enabled rapid advances. AI is being integrated into education, administration, industry, and security infrastructures, reinforcing China’s long-term ambition to reduce dependence on Western technologies while exporting its own systems to a growing sphere of partners.

The resulting global configuration increasingly resembles a form of asymmetric bipolarity. The United States clearly remains the dominant power in artificial intelligence, controlling the most advanced models, the majority of the world’s AI hardware supply chains, and the most widely used global platforms. China, however, is now the only actor capable of mounting a sustained, large-scale challenge across development, deployment, and geopolitical outreach. For the moment, the U.S. advantage is clear. But the speed of China’s ascent suggests that AI has become a central front in a long-term strategic rivalry rather than a temporary technological race.

Within this emerging order, the European Union occupies a distinct position. Europe has established itself as the world’s leading regulatory power in artificial intelligence. Its comprehensive legal framework seeks to ensure ethical standards, transparency, and the protection of fundamental rights. This regulatory leadership has given the EU considerable influence over how AI systems are designed and deployed within its market and, indirectly, beyond it.

At the same time, Europe remains far behind in the development of large-scale, globally competitive foundational models. European initiatives have produced notable research and innovation, but they have struggled to achieve the scale, investment, and infrastructural integration necessary to rival American and Chinese ecosystems. As a result, the European digital space remains heavily dependent on foreign AI systems, particularly from the United States, and increasingly from Asia. As for specific LLM, just the French Mistral can be counted – with less than 4% in the global market share.

This imbalance has geopolitical consequences. Without strong indigenous AI infrastructures, Europe risks becoming primarily a consumer and regulator of technologies developed elsewhere. The continent may shape the rules of AI governance, but not necessarily the technological realities to which those rules apply. For European societies, this raises questions about economic sovereignty, data control, and long-term strategic autonomy.

Beyond the three main poles, other countries are also positioning themselves within the AI landscape. Japan and South Korea continue to play important roles, particularly in robotics, electronics, and applied AI, though their ecosystems remain closely intertwined with American platforms. The Gulf states are investing heavily in sovereign AI capabilities and regional data infrastructure, aiming to secure strategic autonomy rather than global dominance. India is rapidly becoming one of the world’s largest AI user bases and talent pools, suggesting a future role of growing importance, even if frontier models are still largely developed elsewhere.

By early 2026, patterns of AI use confirm that technological power does not simply follow population size or consumer numbers. Strategic influence is concentrated where models are trained, where chips are produced, where cloud systems operate, and where AI is embedded into the software infrastructures of other industries. On all of these levels, the United States retains a decisive lead, while China is building an increasingly coherent alternative sphere.

The geopolitics of artificial intelligence is therefore no longer a speculative theme. It is an active process reshaping economic systems, technological dependencies, and international alignments. For Europe, the central challenge is no longer only how to regulate AI responsibly, but whether it can develop the capacity to participate as a full strategic actor in a world where intelligence itself is becoming a contested resource.

In this new global balance, AI is not merely a tool. It is rapidly becoming part of the underlying cognitive infrastructure of modern societies. Nations that design and control this infrastructure will shape the conditions under which others innovate, govern, and even think. The question confronting Europe, and much of the world, is not simply who builds the best models, but who ultimately defines the technological foundations of the coming decades.

This article is translated with AI.